Ephemeral Renaissance

The Ephemeral Renaissance collection unites all manner of single-sheet imprints and broadsides from throughout the early modern period (ca. 1490-1760). Together, this remarkable gathering of several hundred items not only illustrates the vast array of genres and modes of ephemeral print production from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment; it also provides a unique snapshot into single-sheet printing as a distinct form of knowledge production, often with very specific characteristics. Many are occasional and time-bound linked to triumphal entries in the great cities of Europe, major festivals, royal weddings, and the elections of popes in conclave. Others report on epic battles, diplomatic occasions of note, and the erection of edifices: fountains, monumental columns and obelisks, palaces, churches, and cathedrals.

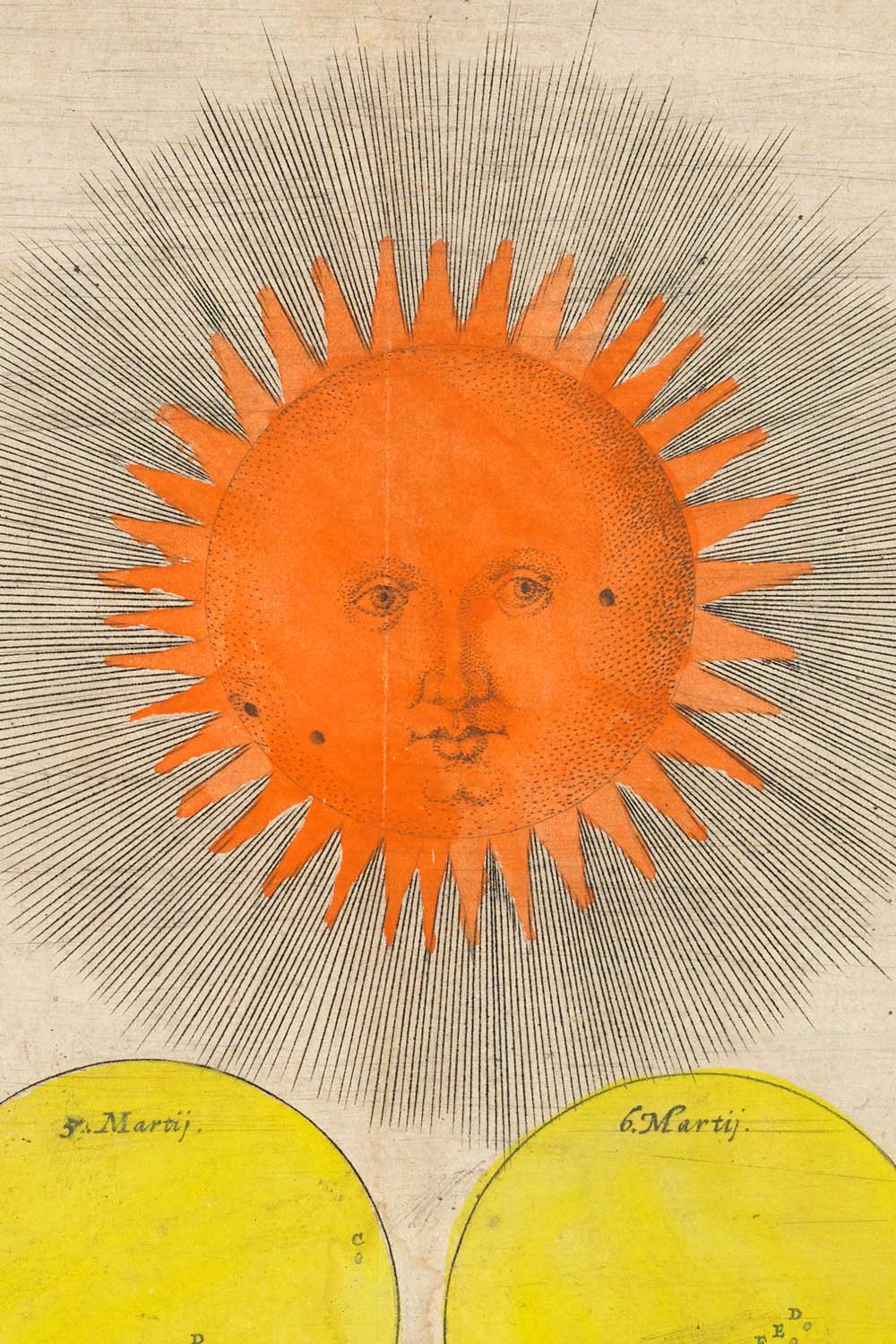

Many items in the collection also serve a distinct and often explicit memorial purpose, as keepsakes for travelers and antiquaries, announcements of dissertation defenses, diplomas, major anniversaries, from mundane wedding licenses and monachization poems celebrating the investiture of nuns, to somber obituary memorials, to grand confraternity charters. Others seek to spread news of momentous events from scientific discoveries, to great fires in the metropolises of Europe, to landmark technological innovations. Paper tools abound as well, from never-made globe gores, broadsheets bearing volvelles, and even a sheet designed for use as a sundial. Many, indeed the majority, are also illustrated, leveraging the native human interest in images and revealing that it was not only books could be read by their covers.

Assembled according to an acquisition principle that privileges form over content, the Ephemeral Renaissance collection makes visible a comparative set of printing and distribution practices that can hardly be recognized by those who have tended to treat single-sheet imprints in isolation (as is so often the case). While some items in the collection luxuriate with intricate engravings by master artisans, others communicate directly with clear, unadorned prose pointing more squarely to a broad and pecuniary public readership. Every object in the collection contains text of some sort, distinguishing it from more traditional fine art print cabinets assembled more often by museums than libraries and archives. In each of these ways, the Ephemeral Renaissance Collection stands as a kind of archive that provides a rich body of evidence about how texts were presented and circulated outside of the confines of the traditional bound volume. At the same time, perhaps ironically, many survive today only because their former owners had the presence of mind to fold them and preserve them inside the safety of well-bound books.

Another hallmark of this engagingly eclectic collection is the sheer rarity of the materials. A substantial minority of Ephemeral Renaissance collection items are, except for the JHU copy, unrecorded and heretofore unknown to modern scholarship. In many instances, where another copy is known, they are only recorded in a handful of copies, with rarely any available in North America. They are as far-flung as the subject matter that early modern ephemera itself represents, appearing from nearly every major printing center of Europe, in Latin and in the many European vernacular languages, including English, French, Dutch, Spanish, German, and major points besides across the Holy Roman Empire, and even as far as Latin America.

Due to both the occasional nature and scarce survival of these single-sheet prints, we often refer to the formal genre as “ephemera,” a word derived from the Greek etymon ἐφήμερος [ephḗmeros], literally meaning “for a day.” Though useful for conceptualizing the social life of myriad types of objects, this collection helps reveal that the concept of “ephemerality” often oversimplifies the many ways in which any one object announces its manner of production, circulation, and consumption within a socio-economic network of printers, illustrators, booksellers, readers, and collectors. From single-sheet wall calendars and almanacks designed strictly for use within a single year, to folding apotropaic book amulets, to ominous tabloid accounts of monstrous births in the countryside, the ways in which single-sheet imprints become ephemeral are as varied as the objects themselves.

A 1699 auction poster for a Netherlandish galleon with manuscript notes from an inspector and an engraving of a cormorant blown far from the sea and shot down near Nuremburg in 1650 are both ephemeral, but the way in which they functioned and circulated in their own time varied substantially. Indeed, the regular presence of manuscript annotations, and in substantial cases the hand coloring of objects, offer ample evidence of their practical function and orientation within the marketplaces both of books and of ideas. The common presence of marginalia and the frequent investment of many of these objects with religious or supernatural powers (particularly in the Roman Catholic world), reveal historical information and evidence of how people referred and related to, and how they utilized that information over time.

No less integral than the circumstances of their production and use, the materials gathered in the Ephemeral Renaissance collection also ask the reader to consider the circumstances of their own transmission and survival to the present day. While codices hold within them the history of libraries, collectors, bibliophiles, and institutions, ephemera turn our attention to conceptions of waste, of repurposing outdated or obsolete forms of information, and the binding up of like forms of ephemera into eclectic portfolios. Some objects, like the 1490 Almanach und Practica auf das Jahr (a medico-almanac and bloodletting calendar) survive only as binding waste, while others, such Phillipe Galle’s 1577 series the Septem Opera Misericordiae Spiritalia [“Seven Spiritual Acts of Mercy”] seamlessly traffic between the world of fine art and mass production. Some ephemera, such as royal proclamations and municipal advertisements, were tied to single places at specific moments in time, the relevance of which often ebbed into irrelevance soon after their production. Others, such as the aforementioned paper tools and calendars, were bound to a particular activity, or a particular period of time, after which they could be, and evidently often were, functionally destroyed, transformed, or rendered all but useless.

Aware of the peculiar impermanence native to the broadside, engravers and printers alike would often draw attention to an imprint’s own impermanence or temporality within the images and/or text itself. Whenever the River Thames froze over, such as in winter of 1739-40 (as it had in the winters of 1683-4 and 1608 before that) printers set up presses right on the river ice where, for a small fee, a Londoner could have their name printed on a commemorative sheet. One of the four early frost fair broadsides in the collection bearing the name of Simeon Warner is explicit about the occasion, and its unusual circumstance: “Printed upon the Ice, on the River Thames, January the 18th, 1739-40.”

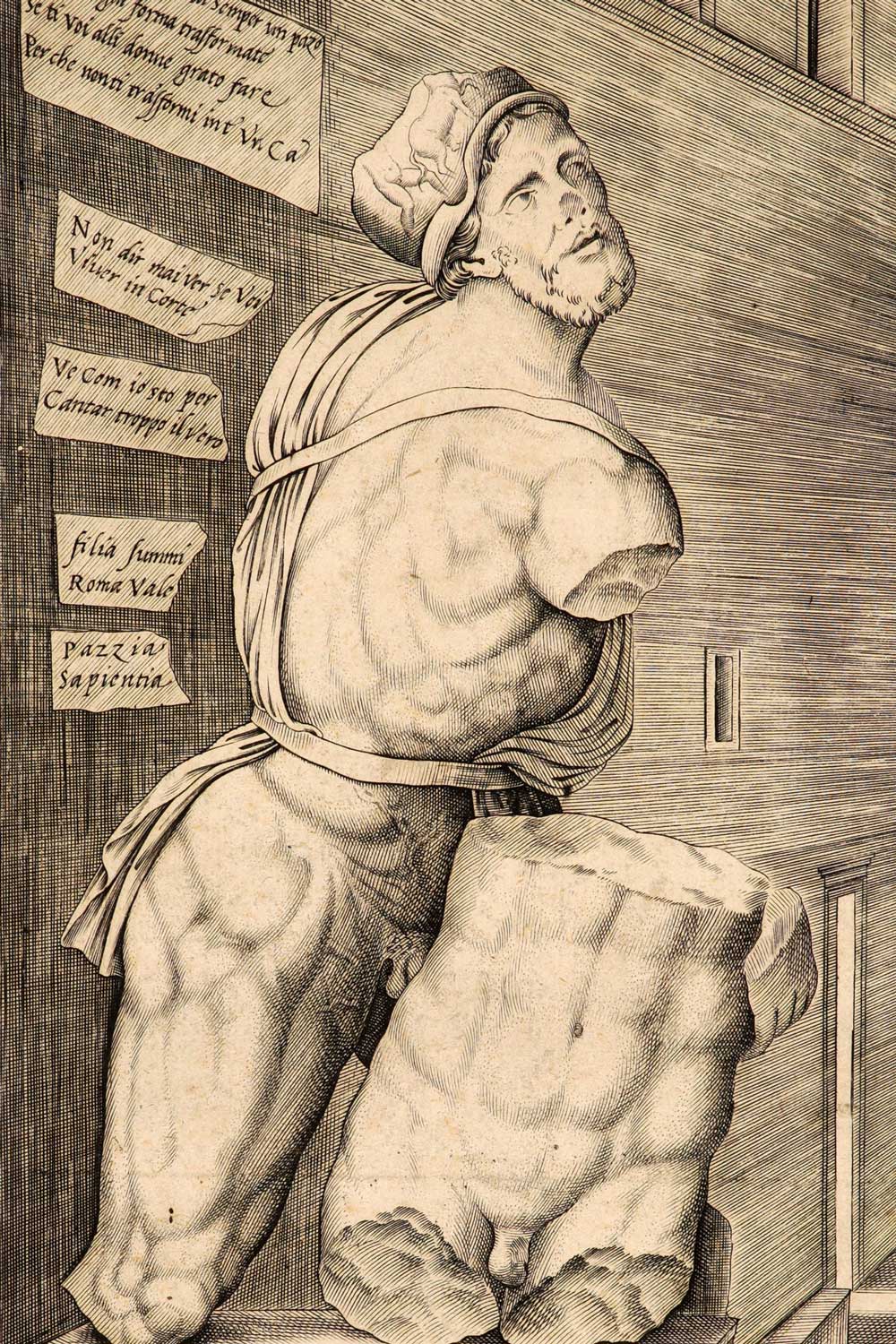

Likewise, the Ephemeral Renaissance collection boasts engravings documenting, and often celebrating, town squares crowded with festival goers, fantastical scenes of multi-year engineering projects collapsed into single, busily overpopulated scene. Major firework displays appear time and again frozen in time on a sheet of paper that itself moves into the marketplace much as a single ember from what had been a grand and unforgettable explosion falls from the sky. Perhaps the most striking example of an ephemeral representation of ephemerality is an engraving of the “talking statue” Pasquino in Rome plastered with fleeting epigrammatic, satirical poems now eponymously known generically as “pasquinades.”

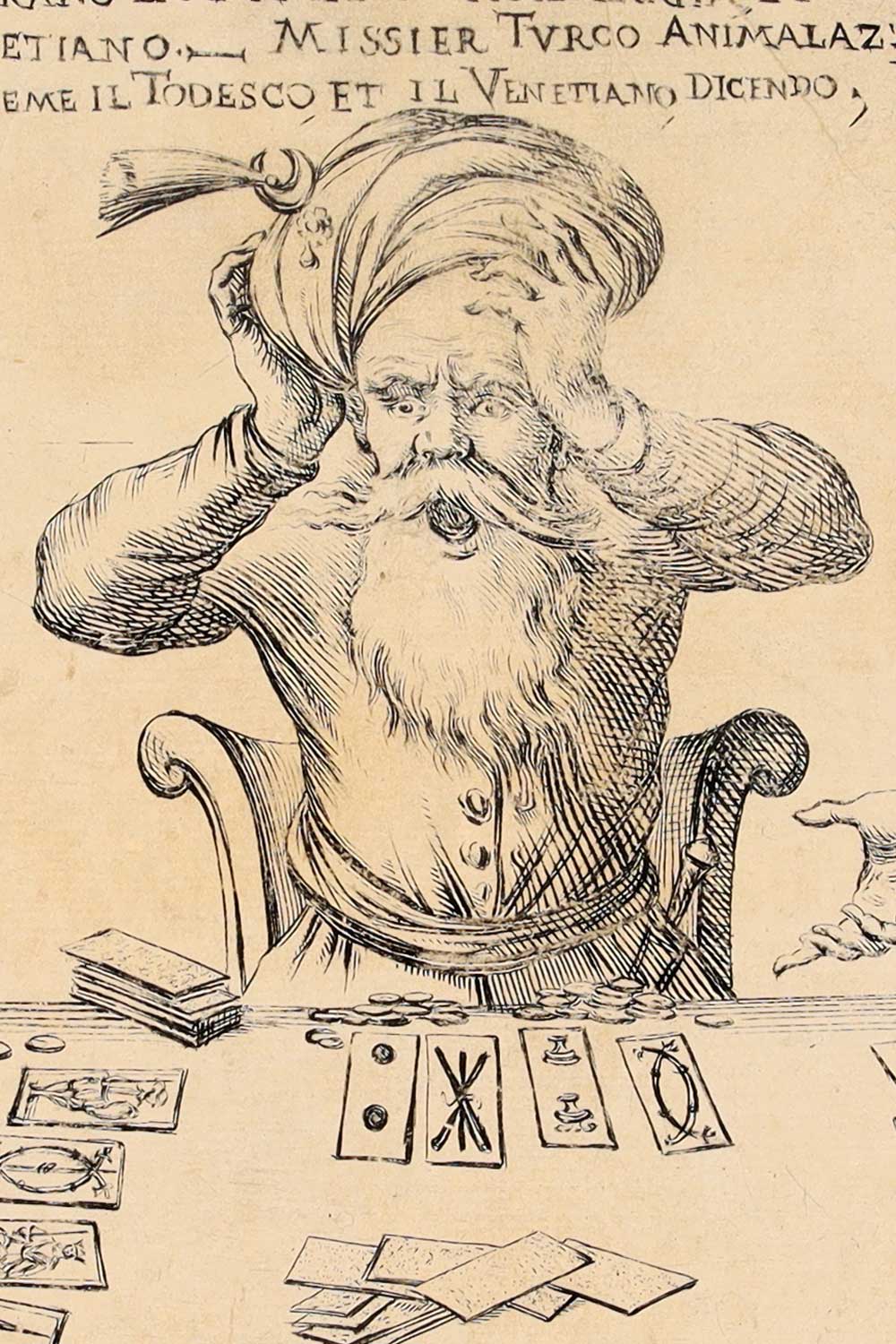

The Ephemeral Renaissance is also especially rich in artifacts of Christian devotion, wartime broadsides, and mundane legal documents ranging in scope from a Bolognese begging license, to a Flemish broadside restricting second-hand book sales in Antwerp, to a Bavarian edict ordering the confiscation of debased coinage during a period of hyperinflation. A majority of the extensive corpus of the seminal late seventeenth-century Bolognese engraver and satirist, Giuseppe Maria Mitelli, is represented in the collection as well, from a strong collection of his earthy but also moralizing board games—some of which even scold the player for even using the game in the first place—to scores of his caricatures of people from all walks of life.

—Daniel T. McClurkin, Earle Havens

Bibliography

Tim Somers, Ephemeral Print Culture in Early Modern England: Sociability, Politics, and Collecting (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2021); Patricia Fumerton (ed.), The Broadside Ballad in Early Modern England: Moving Media, Tactical Publics (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020); Gillian Russell, The Ephemeral Eighteenth Century: Print, Sociability, and the Cultures of Collecting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020); Rosa Salzberg, Ephemeral City: Cheap Print and Urban Culture in Renaissance Venice (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2014); Kevin Murphy and Sally O’Driscoll (eds.), Studies in Ephemera: Text and Image in Eighteenth-Century Print (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2013); Patricia Fumerton (ed.), Broadside Ballads from the Pepys Collection: A Selection of Texts, Approaches, and Recordings (Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Society, 2012); Joad Raymond, The Oxford History of Popular Print Culture, Volume 1: Cheap Print in Britain and Ireland to 1660 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011); Brendan Dooley (ed.), The Dissemination of News and the Emergence of Contemporaneity in Early Modern Europe (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2010); Margaret Ezell, “Multimodal Literacies, Late Seventeenth-Century English Illustrated Broadsheets, and Graphic Narratives,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 51:3 (2008): 357-73; Adam Fox, “Cheap Political Print and its Audience in Later Seventeenth-Century London: The Case of Narcissus Luttrell’s ‘Popish Plot” Collections,” in Roger Chartier (ed.), Scripta Volant, Verba Manent: Schriftkulturen in Europa zwischen 1500 und 1900 (Basel: Schwabe, 2007), 227-42; Joad Raymond, Pamphlets and Pamphleteering in Early Modern Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Joad Raymond, The Invention of the Newspaper (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); John Sommerville, The News Revolution in England: Cultural Dynamics of Daily Information (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996); Peter Stallybrass, “‘Little Jobs’: Broadsides and the Printing Revolution,” in S.A. Baron, E.N., Lindquist, and E.F. Shevlin (eds.), Agent of Change: Print Culture Studies after Elizabeth L. Eisenstein (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007); Tessa Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993); Dianne Dugaw, “The Popular Marketing of ‘Old Ballads’: The Ballad Revival and Eighteenth-Century Antiquarianism Reconsidered,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 21:1 (1987): 71-90; Margaret Spufford, Small Books and Pleasant Histories: Popular Fiction and its Readership in Seventeenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Pres, 1985); David Cressy, Literacy and the Social Order: Reading and Writing in Tudor and Stuart England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980).