Literature

The earliest literary artifacts in the collections of the Sheridan Libraries are papyrological fragments of Homer’s Iliad, including a portion of the famous description of King Nestor’s great golden mixing cup, as well as the Odyssey, all excavated at Oxyrhynchus in Middle Egypt. These are admirably complimented by a rare editio princeps of Homer (Florence, 1489), the first edition to be printed entirely in Greek edited by the scholar Demetrius Chalcondyles. Twenty further sixteenth-century editions and translations of Homer include Aldus Manutius’s historic publication of the separately issued scholia (Venice, 1521), and Johann Herwagen’s innovative arrangement of those same scholia alongside the Greek text in a single volume (Basel, 1523). Other ancient Greek literary authors are represented in numerous early printed editions, including the poets Sappho, Hesiod, and Pindar, the playwrights Sophocles, Euripides, Aeschylus, and Aristophanes, and Hellenistic authors, among them the satirist Lucian of Samosata and the epic poet Apollonius of Rhodes.

Classical Latin literature is amply represented in numerous early editions and commentaries on the poets Virgil, Ovid and Martial, the playwrights Terrence and Plautusand the satirists Juvenal and Petronius. Perhaps the finest single representation of a classical literary figure is the Latin neoteric poet Catullus (who was nearly always anthologized with the elegies of Tibullus and Propertius), with nearly one hundred early editions in the collection. Among more singular treasures in the collection are an early fifteenth-century pecia-style schoolbook manuscript of Virgil’s Eclogues bearing dense marginal and interlinear annotations, and a richly interleaved printed edition of Claudian’s Rape of Proserpine (Paris, 1511) bearing scores of pages of meticulous early sixteenth-century manuscript commentary in French.

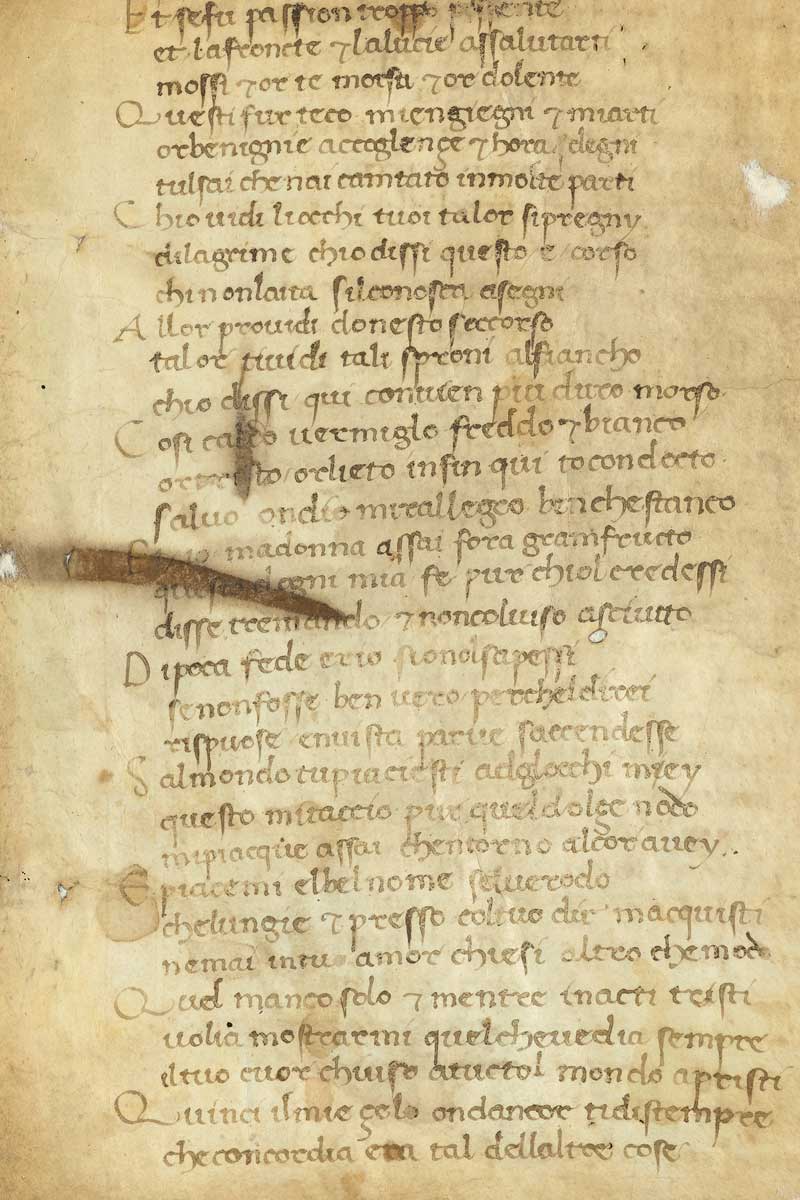

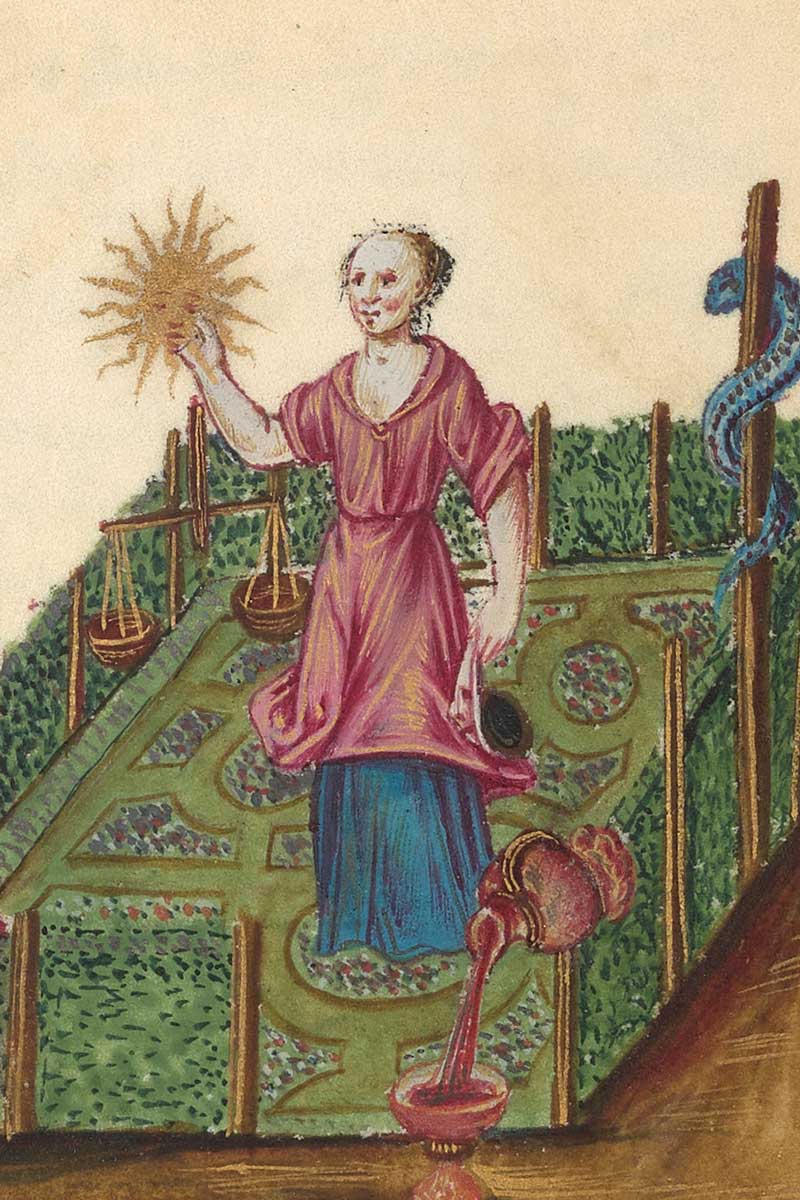

In the realm of medieval literature, JHU holds a substantial collection of early copies of Dante’s Divina commedia, beginning with the 1477 de Spira and 1493 Capcasa editions, and numerous sixteenth-century editions, many of them finely illustrated. Petrarch is similarly well represented in over two dozen fifteenth- and sixteenth-century versions, starting with a noble Quattrocento manuscript fragment of his Trionfi, which is nicely complimented by a printed edition (Venice, 1533) bearing full-page woodcuts of each of the Triumphs. Also notable among these is the first collected Latin prose works of Petrarch, which is also the first appearance in print of his Secretum (Basel: Johann Amerbach, 1496), as well as the 1514 Aldine edition of his Canzoniere and Trionfi, also known as the “Index Aldina” owing to its inclusion of additional poems by other authors quoted by Petrarch—the only vernacular work printed by Aldus twice. The collection boasts fine incunabular editions of Boccaccio’s De casibus virorum illustrium and De claris mulieribus (both 1474), and his very popular Genealogiae deorum gentilium (1487). Among early editions of his Decamerone is the Aldine 1522 edition, which claimed to have significantly stripped away the various editorial errors of prior editions in order to return Boccaccio’s masterpiece to its “original state” (“primo stato”).

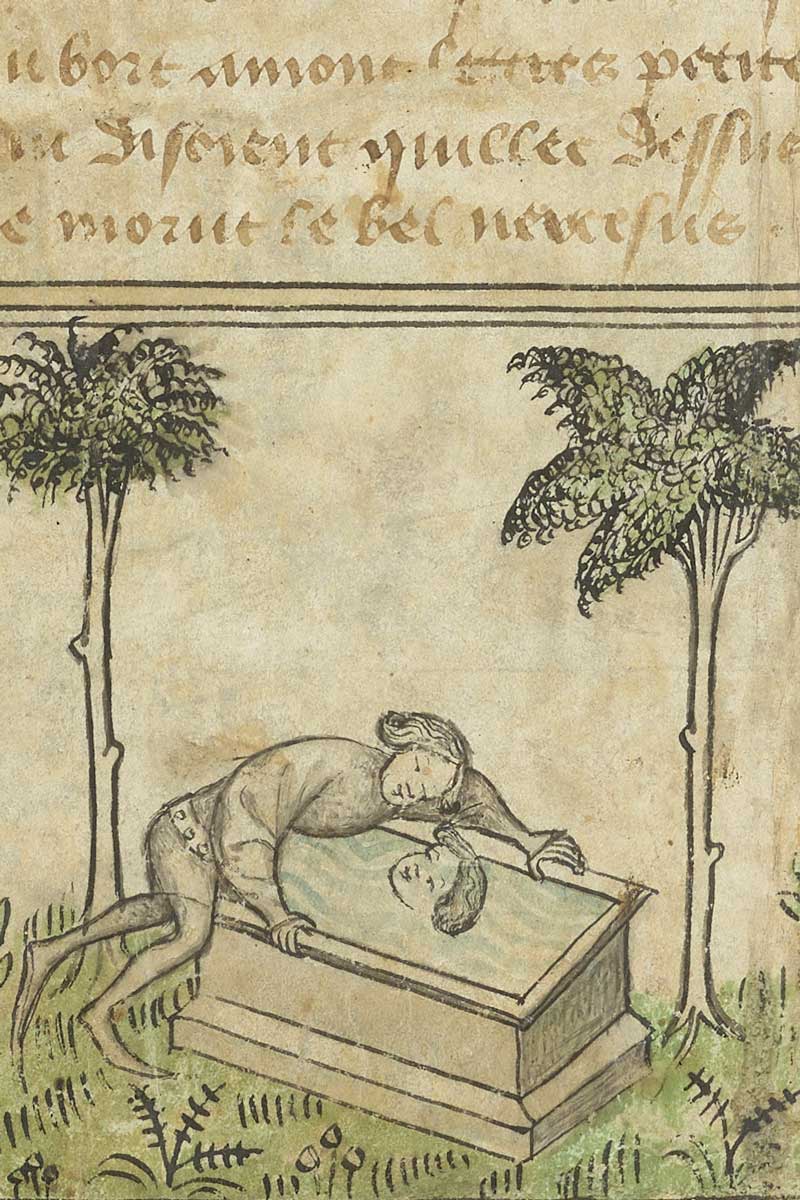

Among the rarest medieval French literary works in the collection is a handsomely printed edition of the court poet Alain Chartier’s Oeuvres (1494?), one of only a dozen copies known, complete with a delightful title page adorned by an extremely early typographical grotesque. During the earlier stages of the digital humanities, JHU lead an international effort to aggregate digital surrogates of some 130 different medieval copies of the Roman de la rose, though it did not actually hold any itself. This was remedied, however, by the fortuitous acquisition in recent years of two fifteenth-century manuscript fragments bearing unusual illustrations, as well as a 1538 octavo printed edition with bespoke woodcuts that was the last Renaissance edition of the poem ever to be printed. While incunabular copies of the literary works of Geoffrey Chaucer, a notable English translator of the Roman de la rose, are impossibly rare, the Sheridan Libraries do hold copies of most of the major sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century editions, including the 1542 Reynes edition with its fanciful architectural title page, and two separate copies of the beautifully illustrated 1561 edition re-edited by the antiquary John Stow—both idiosyncratically endowed with early manuscript homages to the text of Chaucer’s famous tomb inscription. Also present are the 1598 Speight Chaucer, the first to be illustrated with a portrait of the author himself, and the 1602 reprint issued by Adam Islip.

By far the strongest holdings of early works of imaginative literature at Johns Hopkins date from the early modern period. These include one of the finest collection of Siglo de Oro imprints in the US, built from a strong foundation laid in the mid-to-late nineteenth century by one of the earliest Peabody Library Trustees, Severn Teackle Wallis. Of Cervantes’s Don Quixote, the Peabody possesses the third Juan de la Cuesta edition of 1608, the last to appear with corrections during the author’s own lifetime, as well as the 1616 second edition of Part Two of the Quixote which appeared in Brussels just one year after its first appearance in Spain. A later Antwerp edition of 1672 bears extensive manuscript marginalia by the minor English poet Capel Lofft. Among the many important illustrated editions of the Quixote in the collection are the second issue (London, 1620) of Thomas Shelton’s first English translation, with its iconic engraved title page, and possibly the most beautiful edition of all time, the sumptuously etched Bassompierre imprint (Liege, 1776) with its many atmospheric night scenes by the master book illustrators Bernard Picart and Charles-Nicholas Cochin. The dramatic literature of the Spanish Golden Age appears in many early editions of Lope de Vega (1607, 1617, 1618, 1619, 1638, 1644, et seq.) as well as Pedro Calderón de la Barca, including an late seventeenth-century manuscript of eight of Calderon’s occasional autos sacramentales, bearing numerous variations from the Madrid Murga 1717 collected printed edition. These strengths are greatly complemented by the Sheridan Libraries’ extensive collection of over 1,200 comedias sueltas, many of which have been digitized, as well as fourteen examples of that genre in manuscript.

Reflecting Johns Hopkins’ longstanding focus on the Romance languages, each of the major Italian Renaissance poets are amply represented in the library’s collections, in scribal and printed forms, including many illustrated editions, beginning with several early editions of the macaronic verses of Teofilo Folengo, and eight sixteenth-century editions of the works of Jacopo Sannazaro. Ariosto appears in twenty-one early editions and translations, including seven of the Orlando furioso. The library’s early holdings of Torquato Tasso are equally robust, including his very first appearance in print in 1567, and the first illustrated edition of Gerusalemme liberata in 1590. Several of the magnificently illustrated eighteenth-century large-scale editions are also present, including that of Piazzetta (1745). The library abounds with many important Italian as well as French comedies and tragedies. François Rabelais and Michel de Montaigne appear in numerous early editions. Among the scribal treasures of French Renaissance literature is a densely annotated copy of the politically controversial Satyre Menippee (1594), an early manuscript translation of the same into Italian, and a seventeenth-century French scribal adaptation of the emblems of Andrea Alciato.

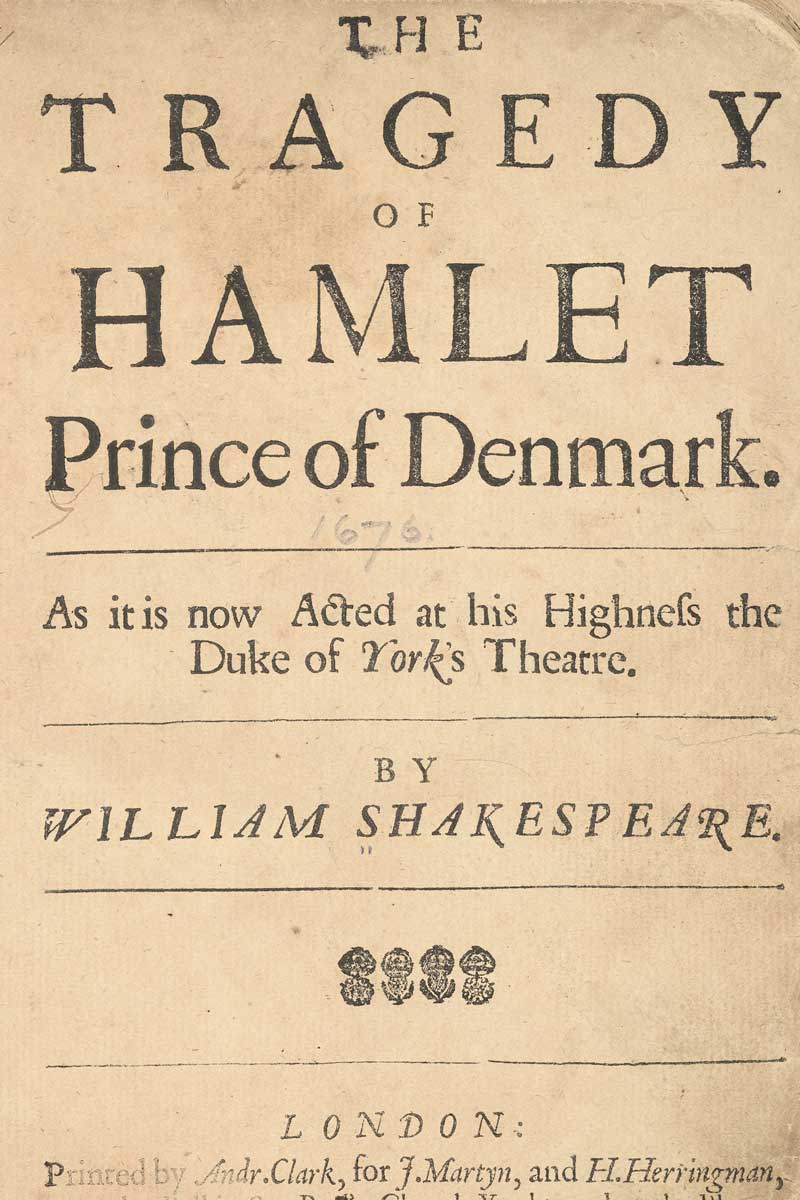

The English literary Renaissance is quite strong at Johns Hopkins thanks in large part to the establishment of the Tudor and Stuart Club (now the T&S Society), and its rare book collection, in 1923. Among the club’s treasures is an impossibly rare copy of Thersytes (c. 1561) attributed to Nicholas Udall and considered to be one of the very first original comedies ever printed in the English vernacular. The university holds copies of all four of Shakespeare’s folios (1623, 1632, 1664, 1685), as well as early quartos of Henry V, The Merchant of Venice (both 1619), and the 1676 Hamlet quarto, just one of three extant quartos to be marked up with extensive manuscript annotations for use as a prompt book. Edmund Spenser, an early focus of the Tudor and Stuart Club, is particularly well represented with five separate Elizabethan editions of the Shepheardes Calendar and the Faerie Queene, respectively, as well as one of the thirteen extant copies of his nuptial song Prothalamion (1596). The library holds both of Ben Jonson’s collected works in folio (1616, 1640), as well as a book from his personal library bearing his autograph signature and motto, Tamquam explorator. Seminal editions of the works of Sir Philip Sidney, Robert Southwell, George Chapman, Francis Bacon, Johne Donne, William Crashaw, George Herbert, John Milton, Thomas Vaughan, John Dryden, and Aphra Behn are all present in the collections.

—Earle Havens