Bibliotheca Fictiva

The Bibliotheca Fictiva Collection of Literary and Historical Forgery is the premier library collection in the world that is dedicated entirely to the subject of textual fakery, imposture, and what has come to be called, however problematically, “fake news.” Totaling nearly two thousand rare books and manuscripts, the collection has been built up over more than a half-century by the antiquarian booksellers, collectors, and book historians Arthur and Janet Freeman. First acquired by Johns Hopkins in 2011, hundreds of additional accessions to the collection have made it very much a “living collection” in every sense of that term.

The Bibliotheca Fictiva spans the entire Western tradition from classical and biblical antiquity to the early-to-mid-twentieth centuries. The criteria for what technically constitutes a “literary forgery”— or, for that matter, a credulous defense or popular demolition of one—can often be challenging to define, not least because precious few studies have treated forgery as a distinctive genre or mode of literary production in its own right. Indeed, no classical “canons” of literary forgery have been handed down to us from the ancients as a counterpoint to the finer points of forensic oratory. True, individual studies abound of famous “ancient” forgeries such as the Donation of Constantine and the Corpus Hermeticum, and of “modern” ones like the imposter William Henry Ireland’s multiple fake Shakespearean “autograph documents,” or the pernicious and anti-Semitic Protocols of the Elders of Zion. These are but a handful of volumes in what Giambattista Vico imaginatively described as the great “museum of credulity” and voluminous “library of impostures” encompassing all of human history. The thousands of volumes that form the Bibliotheca Fictiva comprehend and manifest in profusion what Vico, writing in the early eighteenth century, could scarcely imagine.

Arthur Freeman’s description of his and his wife’s own collecting criteria for the Bibliotheca Fictiva merits extensive but also concise quotation (Freeman, Bibliotheca Fictiva, xi–xii):

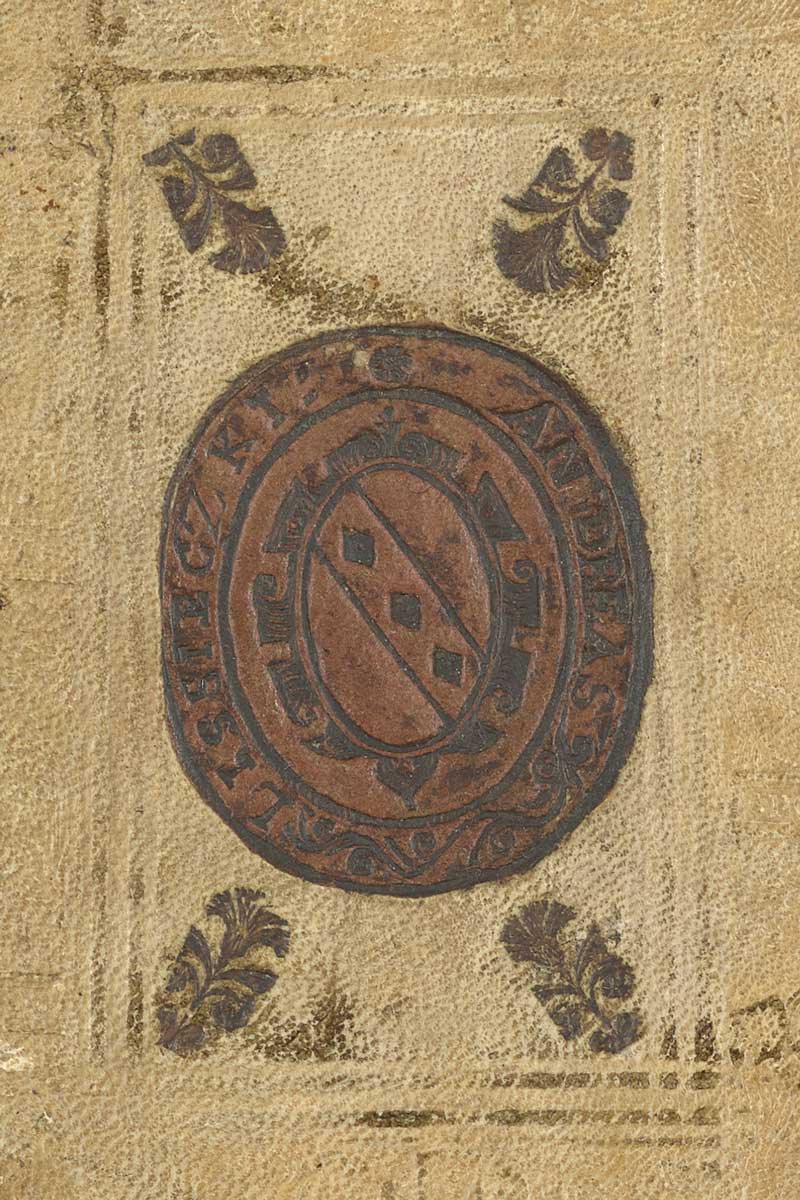

“Accepting a still-intimidating overall brief—the entire range of literary forgery, that is to say the forgery of texts, whether historical, religious, philological, or ‘creatively’ artistic, in all languages and countries of the civilized Western world, from c. 400 BC to the end of the twentieth century—we sought the original publications of such spuria, and their first and ongoing exposures (or obstinate endorsements), in whatever printed editions seemed most significant (along with manuscripts and correspondence when applicable), with a special emphasis, inevitable for us, on evocative annotated and association copies. We admitted specimens of the more conventional physical forgeries—faked printings, falsified provenance and ‘autograph’ annotation, etc.—but our main interest lay not in such bibliopolic and bibliophilic foolery; rather, in the deceptive creation of spurious text and fictive record, and the history of its investigation and discredit, or indeed its survival in present-day controversy.”

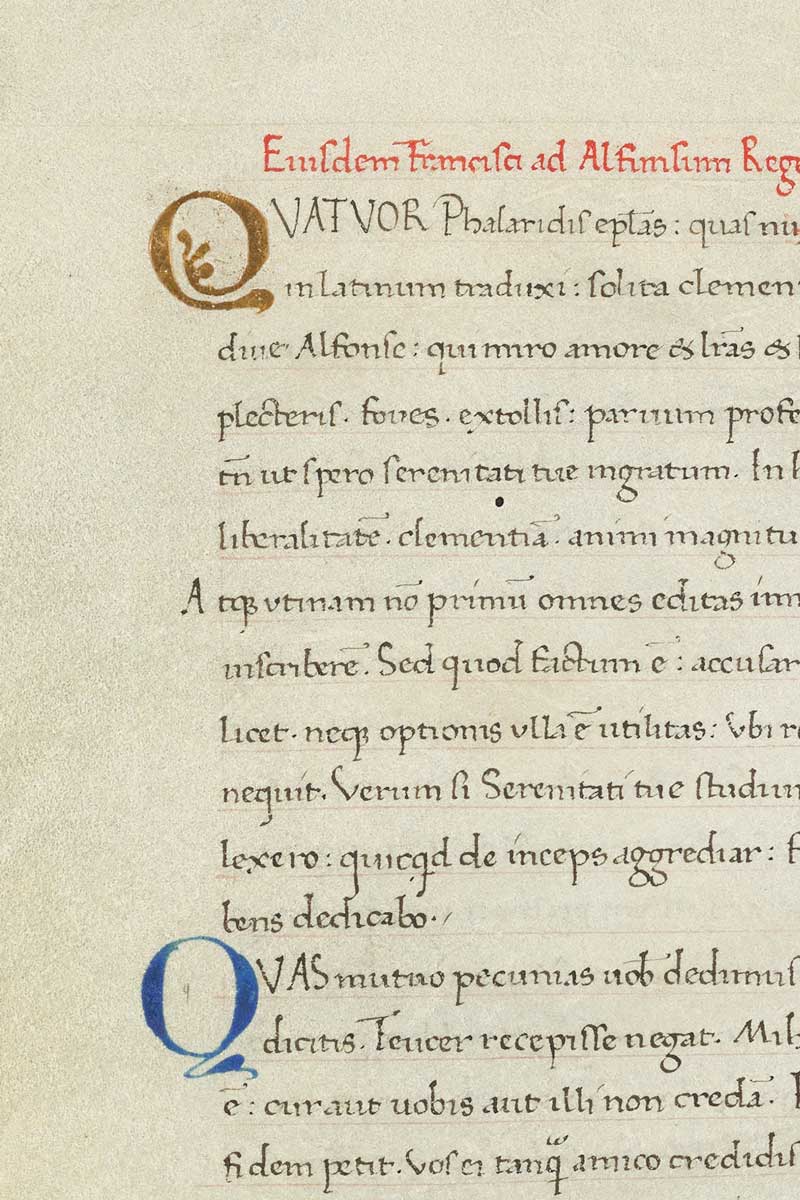

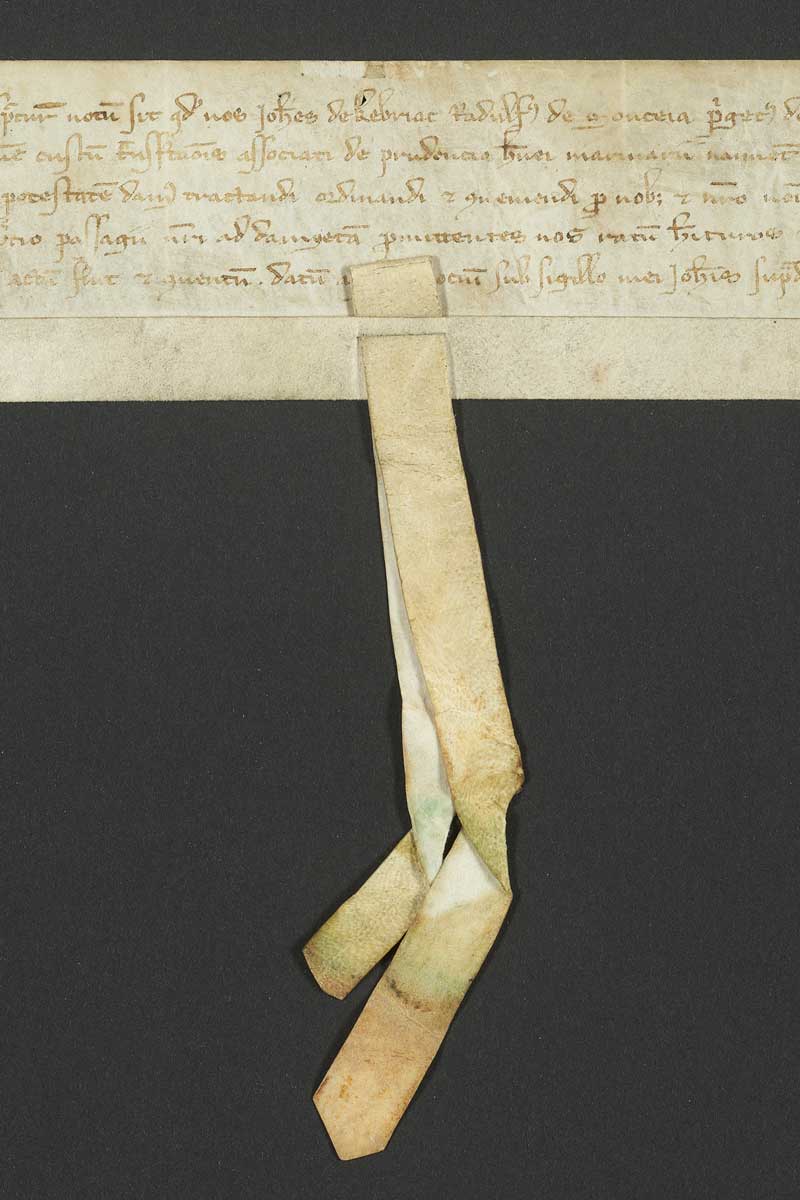

From the first ancient Greek “travel liars,” to the faked epistles of pseudo-Aristeas and Phalaris, fabricated “eye-witness” accounts of the Fall of Troy, and invented epigraphic inscriptions from ancient ruins that never existed, onwards to small oceans of extra-biblical pseudepigrapha—classical and biblical antiquity are amply represented in the Bibliotheca Fictiva. Medieval “monkish” forgeries extend to faked patristic homilies and pastoral letters, false ecclesiastical decretals, and invented acts of early Christian councils. Faked polemics against “Pope Joan” (and their early modern demolition by both Catholic and Protestant critics) sit comfortably on the shelves of the Bibliotheca Fictiva alongside the imaginative, if also often imaginary, chronicles of Asser, Geoffrey of Monmouth, and Godfrey of Viterbo.

The renewed rigor of Renaissance classical scholarship and textual criticism was accompanied by equally ambitious efforts to pour new wine into old bottles, from the “archforger” Annius of Viterbo’s “newly discovered” but impossibly ancient world histories, to Carlo Sigonio’s “lost” Ciceronian treatise on death, and Curzio Inghirami’s scarith “time capusules” claiming to reveal the lost lore and prophecies of the last Etruscans. The Baroque and Enlightenment eras proved to be just as fertile for forgery, including devastating demolitions of several of the most enduring ancient forgeries (the Donatio Constantini, Corpus Hermeticum, and the Sibylline Books, to name but a few) and imaginative concoctions of others, including an Elizabethan invention of Anglo-Saxon laws as precedents for contemporary trade protectionism, and the runic “facsimile” of the fake Icelandic “Hjalmar” saga.

Literary plagiarism and opportunistic false attributions allowed would-be hack writers to capitalize on the success and fame of actual best-selling authors including, among their many victims, Samuel Butler, Laurence Sterne, and Henry Fielding to name but a precious few. So too must be counted the inventions of William Lauder—the would-be critic who falsely “exposed” Milton’s Paradise Lost as plagiary—Thomas Chatterton’s fatal “Rowley Poet” impostures, and James Macpherson’s incredibly popular, and incredibly fake, verses of the “ancient” Celtic bard “Ossian.”

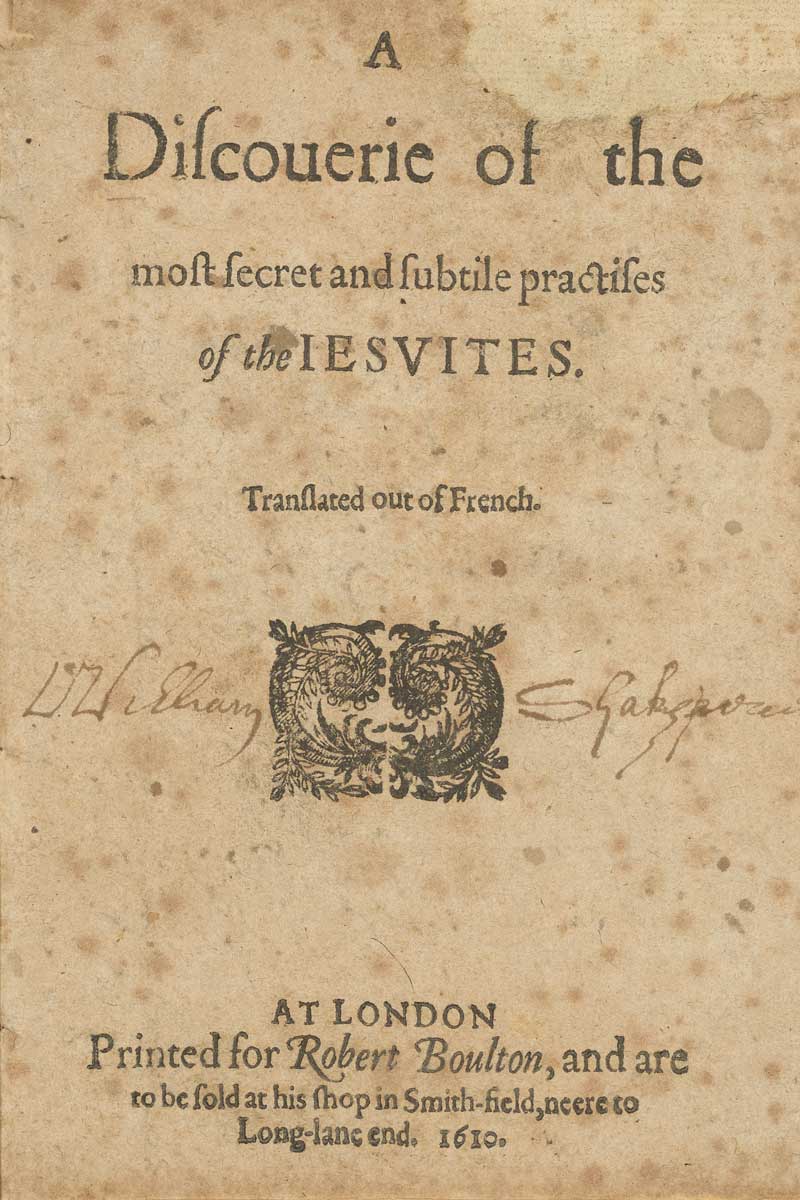

With the advent of “bibliomania” in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a new brand of pecuniary forgery emerged, purporting to put into the hands of eager, if also impressionable, book collectors literary artifacts that were definitively “too good to be true.” False “autograph” verses purportedly by Martin Luther and Ben Jonson, forged letters alleged to be by William Shelley, and “inscribed” books from the personal library of Lord Byron were all invented by a host of con artists happy to cash in on a sometimes red-hot trade in antiquarian books and literary “contact relics.” From the sublime to the ridiculous, the Bibliotheca Fictiva also tracks the deceptions of scholar-forgers like John Payne Collier, who mixed convincing fakery with authentic evidence in manuscript and printed forms, and the follies of bibliophiles so eager to bid on impossibly rare books listed in the fake Fortsas auction catalogue that they traveled to attend this well-advertised but nonexistent sale in the tiny provincial Belgian village of Binche.

Latter-day impersonators like “Princess Caraboo” and the Baltimore-born Bata Kindai Amgoza ibn LoBagola, whose persona as a self-described as an “African Savage” and descendant of the lost tribes of Israel, occupied their moments in the popular imagination for years. So, too, did the the racist “miscegenation pamphlet” hoax that sought (unsuccessfully) to bring down Abraham Lincoln’s antislavery Republican party, and the writings of the preposterous eccentric Charles Otley Groom-Napier, whose invented titles of Prince of Mantua, Montferrat, Ferrera, Nevers, Rethel, and Alençon were nearly as elaborate as his published pseudo-scientific vegetarian cures for dipsomania. Nineteenth-century manuscript fakes—such as Constantine Simonides’s antiqued and “ancient” Greek manuscript on vellum revealing the mysteries of Byzantine painting, and a false thirteenth-century French Crusader charter designed to qualify several French families’ arms for prominent display in Louise Philippe’s Salles des croisades at Versailles— demonstrate the eternal human desire to discover “lost” works. A fine gathering of medieval illuminations on actual early parchment fragments by the so-called Spanish Forger and his imitators fed the appetites of art collectors eager for more traditional alternatives to latter-day expressionist and surrealist works. False memoirs, such as Friedrich Nietzsche’s My Sister and I and William Mannix’s spurious Memoirs of Viceroy Li Hung Chang, are further standouts among the more colorful early twentieth-century holdings.

The Bibliotheca Fictiva has enjoyed a welcome reception at Johns Hopkins and beyond, including a major exhibition at JHU’s George Peabody Library in downtown Baltimore and an allied exhibition catalogue (sold out and reprinted in a revised second edition), a complete item-level printed catalogue (a further Continuation of which, enumerating all the additions made to the collection in the past decade, was published in 2024), and several semester-long courses taught at the undergraduate and graduate-student levels. A segment of National Public Radio’s Saturday Edition with Scott Simon, offers an introduction to the collection, as well as several magazine articles, including the Johns Hopkins Magazine and Fine Books & Collections. An international conference convened at JHU also resulted in a volume of essays inspired by the collection being published by the Johns Hopkins Press. One hundred of the earliest and rarest books in the Bibliotheca Fictiva have just been digitized and made freely available on the Internet Archive, with the support of generous grant funding from the Arcadia Fund, with the hope of much more digital access being provided to the full collection in the coming years. All items in the Bibliotheca Fictiva are also accessible through the JHU online catalogue and Hopkins archival finding aids.

—Kelsey Champagne, Earle Havens

Bibliography

Arthur Freeman, Bibliotheca Fictiva: A Collection of Books and Manuscripts Relating to Literary Forgery, 400 BC–AD 2000 (London: Bernard Quaritch Ltd, 2014); Walter Stephens and Earle Havens, assisted by Janet Gomez (eds.), Literary Forgery in Early Modern Europe, 1450–1800 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018); Earle Havens (ed.), Fakes, Lies, and Forgeries: Rare Books and Manuscripts from the Arthur and Janet Freeman Bibliotheca Fictiva Collection (Sheridan Libraries, 2014; 2nd ed. rev., 2016); Earle Havens, “Forgery” and “Plagiarizing,” in Ann Blair, Paul Duguid, Anja Goenig, and Anthony Grafton (eds.), Information: A Historical Companion (Princeton University Press, 2021), 458–63, 659–64; Dale Keiger, “Sham Text,” Johns Hopkins Magazine 64:3 (Fall 2012), 44–49; Earle Havens, “Bibliotheca Fictiva: The Arthur and Janet Freeman Collection of Rare Books in the History of Literary Forgery,” Fine Books & Collections Magazine 12:4 (Autumn 2014), 54–59; https://www.npr.org/2014/11/29/367338707/jesus-started-the-first-chain-letter-and-other-hoaxes; https://archive.org/details/bibliotheca_fictiva.